First of all, thank you for taking the time to click on this. I’ve found myself frequently having longer form comments and thoughts about things that are going on with the Cleveland Guardians, and Twitter just isn’t a conducive format for communicating those thoughts. So not only is this an outlet for that, it’s also a way for me to save your timeline from me posting 10 tweet threads every time I have something to say.

Today, I thought I’d do a little bit of a deep dive into something I’ve noticed about the Guardians’ offensive struggles as well as what seems like a new approach to acquiring and developing players to combat those struggles. I particularly want to address how Chris Valaika fits into all of this.

For the record I don’t think that Valaika is necessarily the progenitor of this new philosophy, but rather was hired because the FO was already adopting this philosophy, and he fit what they were looking for.

So with that said, buckle in, because there’s A LOT to talk about here.

Let’s talk about Chris Valaika and 2022

Chris Valaika has been the Guardians’ hitting coach since the beginning of the ‘22 season. A season that saw them win 92 games and come within a game of an ALCS appearance. The 2022 Guardians were fun. They saw 17 players make their MLB debut, the most of any playoff team in history. They became known for a “disgusting brand of baseball,” which is another way of saying they hit bloop singles, ran the bases aggressively, and rode the razors edge of BABIP luck to 29 wins in their last at bat (breaking the team record of 27 set by the legendary 1995 team), while Valaika was lauded for “fixing” the offense from the previous year. Like I said, it was a fun team, but when you look under the hood the flaws start to become pretty apparent.

First off, the 2022 Guardians were not a good offense, they were an average one. They ranked 15th in offense, 29th in home runs, and 21st in SLG. The only thing they truly seemed to do well was get the hit when it mattered, something that is entirely up to chance and sequencing, not something that can be replicated. None of their offensive statistics were in any way exceptional. The “disgusting brand of baseball” was a fun story, but the 2022 Guardians were, at their core, a team with elite pitching (particularly in the bullpen) that hit the ball just well enough to get by.

2023, on the other hand, has been a disaster offensively.

Let’s talk about 2023.

Let’s face it, the Guardians’ fan base hasn’t agreed on much this year. There has been debate after debate about every player, every coach, and every transaction. From the “it’s still early” crowd to the Amed Rosario discourse and the “fire Tito” movement every issue this year seems to split the fan base.

However, if there’s one thing every serious fan can agree on this year, it’s how bad the offense has been.

Beyond being the team’s biggest issue, it seems to be the one that every other debate is rooted in.

You hated Amed Rosario? It was probably because you were tired of watching him swing at sliders that almost hit Sandy Alomar in the first base coaching box.

Loved Amed? You probably saw his occasional 4 hit outbursts and thought “we can’t afford to take this out of our lineup”

Want to fire Tito? Chances are it’s because “9. Straw CF” showing up every single day is making you sick to your stomach knowing that they’re willing to let the worst qualified hitter in baseball start 95% of the games and somehow find a way to be the guy at the plate in every key AB this year.

Hate Tito’s bullpen management? Wouldn’t matter as much if the offense could put a team away, or if the Guardians weren’t playing in the 2nd most one-run games in all of baseball.

You see where I’m going with this? Every single problem the Guardians have traces back to one aspect of the team, the offense. You may be asking, what’s wrong with our offense?

We have ZERO power.

In today’s game, SLG = Runs, and Runs = Wins. Of the top 10 run scoring teams, only 2 are outside of the top 10 in SLG, and they’re both top 15. Every team that would be in the playoffs right now is top 15 in runs, except for Minnesota who doesn’t really count because the AL Central is so bad.

Cleveland bottom 5 in baseball in runs scored (448) and SLG (.383), and dead last in home runs (82). They’re not hitting for power, therefore they’re not scoring, therefore they’re not winning. It really is that simple. If you’ve been following the Guardians for any amount of time this year, none of this is new to you.

With the offensive struggles, Chris Valaika has shouldered much of the blame, especially for the regression of some key players (particularly Andrés Giménez). Fans have noticed the team not only struggle to hit for power, but seem like they’re actively prioritizing making contact over hitting the ball with any authority. All the while, expanding the zone and chasing regularly in the interest of “just put the ball in play at all costs.”

It’s a logical conclusion that the blame for this approach and the ensuing struggles belongs at the feet of Valaika. After all, he is the hitting coach and we’re talking about the failures of the hitters. The assumption by fans is that Valaika watched Bull Durham and heard Crash Davis’ famous line “Strikeouts are fascist” and, not wanting to be perceived as fascist in today’s political climate, made it his life’s work to ensure that nobody he coached ever struck out again.

Between this year’s struggles, the “digusting brand of baseball” from last year, and the Guardians apparent talent acquisition preference for high-contact, low-power offensive profiles, it seems as though Valaika is the posterchild for the new approach the Guardians organization has for offense. The common opinion amongst fans seems to be that the Guardians either can’t, or don’t have an interest in, developing power.

However, upon closer review, I don’t believe this to be the case.

Let’s talk about where power comes from.

The first, and most important, thing we need to talk about is that this idea that contact first hitters “develop” power. While there are exceptions (and we will investigate those) when you look at the list of the top power hitters in the game, nearly every single one was scouted as having a “plus” grade for power.

Of the top 10 hitters this year by Slugging %, here’s where they ranked on the 20-80 scale for their “power” tool according to MLB Pipeline.1 In the 20-80 scale, 50 is league average, anything over 60 is excellent (every 10 points on the scouting scale = 1 standard deviation from the average of 50)

70+:

Shohei Ohtani

65:

Ronald Acuña Jr, Luis Robert Jr, Juan Soto

60:

Matt Olson, Kyle Tucker

55:

Corbin Carroll

45:

Mookie Betts

No grade available (made debut before 2012):

J.D Martinez, Freddie Freeman

So of the 10 players with the highest Slugging % in the league only one, Mookie Betts, was scouted initially as having below average power.

Even if you expand this out to the top 20, it still holds true.

10 players were graded at 60+

17 of 20 graded 50 (MLB Average) or better2

6 of 20 graded 50 or Below

It’s pretty clear that by far the best way to add slugging to your team is to get guys that just flat out hit the ball harder than everyone else.

But what about those 6 guys that graded out as average or below? What has enabled them to find success where other players with similar skillsets haven’t?

That’s what we’re here to investigate.

The 6 players who graded out <50 are:

Christian Walker

Isaac Paredes

Mookie Betts

Yandy Diaz

Ketel Marte

Ozzie Albies

For the purposes of this exercise, we’re going to treat Yandy Diaz as an anomaly, because though he was scouted as not having elite power, one day he started looking like this and putting up 99th percentile exit velocities. So while the scouting report might have said he didn’t have much power, this picture begs to differ.

So for the other 5 players, how did they develop into high slugging % hitters without waking up one day looking like they stepped out of a comic book?

To answer that we need find out what they have in common. First, we’ll take a look at batted ball data.

Across the league, balls in play have a slash line of .333/.329/.553/.882.3 While .553 might sound like a rather high SLG, and one that high will usually lead the league if a player were to maintain that percentage for a whole season, keep in mind that these stats are basically looking at what a player’s numbers would be if you got rid of every at-bat that ended in a strikeout or a walk, it’s going to skew higher than what a normal stat line would look like. We’ll be using these numbers (particularly SLG and OPS) as a baseline to compare the different batted ball types to what is “average”

There are 9 different batted ball types represented by the combinations of the 3 launch angle types (Groundballs, Line Drives, Fly Balls) and the 3 spray directions (Pull/Center/Opposite field). We’re going to look at the slash lines for each of those individually, as well as the 9 combinations.

Pull: .345/.343/.655/.998

Center: .330/.326/.489/.815

Oppo: .317/.312/.470/.781

Flyball: .230/.225/.687/.912

Pulled flyball: .419/.412/1.459/1.871

Center flyball: .201/.196/.539/.735

Oppo flyball: .136/.133/.330/.463

Groundball: .244/.244/.267/.511

Pulled groundball: .189/.189/.221/.410

Center groundball: .266/.266/.271/.537

Oppo groundball: .439/.439/.478/.918

Line drive: .706/.701/.916/1.617

Pulled line drive: .714/.709/1.027/1.736

Center line drive: .711/.707/.840/1.546

Oppo line drive: .688/.681/.845/1.526

By now you’re probably thinking “dang, that’s a lot of numbers,” and, to be fair, you’d be right.

But these numbers paint a pretty interesting picture that we can pull a couple of general rules from.

It’s better to pull the ball than hit it to the opposite field (eat your heart out Rick Manning)

It’s best to hit line drives (obviously) but it’s better to hit flyballs than ground balls.

Even more than any of the line drive profiles, the best batted ball profile by both SLG and OPS at an astonishing 1.459 slugging percentage, and 1.871 OPS are pulled fly balls

In general, we want to hit as few balls on the ground, and as few balls to the opposite field as we can

Even though oppo/grounder is the best grounder type, its OPS is still barely above average, best to just avoid both as much as possible.

It appears that avoiding the bad outcomes is just as important as seeking the good ones.

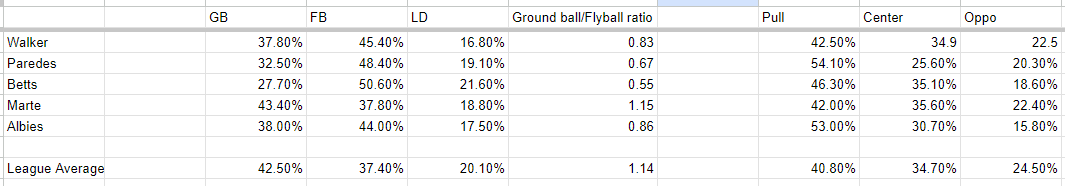

So back to our OPS leaderboard from earlier and the 5 players outperforming their power projections. Please direct your attention to my hastily made spreadsheet below.

With the exception of Ketel Marte, who notably has developed into a guy that consistently puts up some of the highest exit velocities in the game, all 4 of the others have a few things in common

They all hit more fly balls than ground balls

They all pull the ball more than the league average

They all hit the ball to the opposite field less than the league average.

Coupling this with what we just learned about batted ball data, the conclusion is pretty simple.

There are two ways to develop power.

Learn to hit the ball harder (very hard to do)

Learn to pull the ball in the air

As I mentioned earlier, it’s also just as important to hit fewer ground balls and fewer balls to the opposite field as it is to pull the ball in the air more. Increasing your fly ball rate by decreasing your line drive rate won’t have the same positive effect as doing so by decreasing your groundball rate. In the same sense, increasing your pull rate by decreasing your center rate won’t be as nearly as beneficial as doing so by decreasing your oppo rate.

This last piece is purely speculation as I don’t have access to enough data to verify, but I suspect that when you look at players who are scouted with high “raw power” but never achieve a high rating in “game power” that what you’ll find is batted ball profiles with a lot of ground balls, and a lot of balls to the opposite field.

Now back to the Guardians:

As I mentioned at the very beginning, my reason for writing this was to explore a shift that I’ve noticed in the last two years in the Guardians’ philosophy of offensive talent acquisition and player development as well as Chris Valaika’s role in all of this.

To me, it’s abundantly clear that there’s been an organizational shift in philosophy. I know the consensus fan opinion is that the Guardians value a contact first approach, and are eschewing the conventional wisdom of modern baseball by not seeking to develop guys that can hit the ball over the fence, and are deathly afraid of guys who frequently swing and miss. But, to be honest, I don’t know how true that is, it may have been the approach from 2017-2021 when it seemed like we exclusively targeted 5’10 170lb shorstops with zero power potential, but I think that they made a significant change to that philosophy when they let go of Ty Van Burkleo and brought in Valaika, it just hasn’t quite paid dividends yet. Based on the data I’m looking at, I’m confident it will.

We’re going to dive into player development and talent acquisition separately, but before we do I want to emphasize a few points about where we stand today.

Though we do currently have a contact driven approach, it’s important to remember that not one player currently on the roster (of the guys we at least partially developed) was acquired by the organization after we hired Chris Valaika. And all of them are playing like the players they were scouted to be, none of them have failed to develop power that they were expected to have. They just weren’t expected to have any.

The top prospects aren’t here yet. The guys we’ve been hearing about for years like Bo Naylor, Valera, Freeman, Arias, Rocchio, etc. are just now getting to a point where we can expect to see them take on regular roles at the big league level. The guys that have been here weren’t the cream of the crop guys (except Josh Naylor and Andrés Giménez) that had big expectations.

Valaika and the FO are absolutely insistent that they aren’t ignoring power in the pursuit of contact as evidenced by this quote from Zack Meisel’s interview with the Guardians’ hitting coach4

The goal is never to string together singles. We’ll take it. We don’t preach, “Hit singles.” We want slugging just as much as anybody else. With the identity and makeup of the team, it’s something we don’t want to hide behind, either. We make contact. We also don’t want that to be our Achilles’ heel, that we’re giving away at-bats because we can make contact. So continuing the message to these guys to get their swing off, look to do damage early in the count and then having the ability to tone it back down with two strikes or whatever the game state may be. We’ll take those innings where we put up five runs hitting singles, but it’s definitely not something we’re harping on.

Talent Acquisition

To me, it has become clear that the Guardians have recognized the trend in the batted ball profiles we discussed earlier, and it’s clear that those trends represent a market inefficiency. Guys with big power grades have been sought after since 1920 when Babe Ruth discovered that they can’t catch it if you just hit it over the fence. Beyond the fact that they contribute to wins, they sell tickets, jerseys, and sponsorships. Guys with power aren’t easy to acquire, because there aren’t that many of them, and they are just so valuable to a team.

So, what does a smart front office do? They recognize that the goal isn’t power, the goal is slugging percentage, and through the right types of batted ball profiles you can dramatically outperform expectations in power production, while taking risks to acquire traditional power profiles when they can.

So let’s take a look at our first round picks + the trades we’ve made involving young players in the last 2 years.

First the trades.

Since the start of 2022 we’ve acquired position players Juan Brito, Kyle Manzardo, Bryce Ball, Kahlil Watson, and Justin Boyd via trade

Brito, Watson, and Manzardo were both targeted in 1:1 swaps (Jean Segura doesn’t count), so it’s safe tosay the organization clearly values something they bring to the table.

What is it that all 3 guys do well?

Simple. They all have pull rates north of 50%, they both have cut their oppo rate year to year, and all three of them project overwhelmingly as fly ball hitters, approaching 45-50% fly balls this season.

For more on Kyle Manzardo I’d highly recommend reading this article by Matt Seese. He does a deep dive into Manzardo’s offensive profile, and it’s fascinating

I, on the other hand, would like to focus on Juan Brito. Brito has not only increased his fly ball rate, but since last year he’s cut his infield fly ball rate (popups) by 10 percentage points! Meaning not only is he hitting more fly balls, but they’re going to the outfield more. Brito has rocketed up Guardians prospect lists this year as a result and has quickly won over almost every single person who follows the farm system. The dude just flat out hits.

Who did we give up to get Brito? Nolan Jones. While this trade has drawn the ire of many fans, let’s look at Jones’ batted ball data. He’s put up a GB/FB ratio of 1.5:1 across all levels as well as consistently putting up oppo rates above 35% in the minors. It’s possible that the Guardians saw Jones as someone who despite his immense raw power, wouldn’t be able to get to it enough in games to ever truly become productive. Whether that ends up being the case or not, Brito’s profile is significantly more encouraging than Jones’.

So what about those other two trades?

While Bryce Ball was by no means a high profile acquisition, traded to the Guardians for cash by the Chicago Cubs, it’s certainly interesting that he was putting up career high Fly ball and Pull numbers while putting up career low Ground ball and Oppo numbers this year when we traded for him. A game changing trade? Definitely not, but it is a savvy one with little risk attached, and it fits with what appears to be our new player acquisition philosophy.

Which just leaves the Will Benson for Justin Boyd and Steven Hajjar trade. Admittedly this one has me stumped. Boyd has not played well in his limited sample size and doesn’t fit the profile we’re discussing while Benson may the posterchild for that profile. It’s worth pointing out that Benson was *regressing* in terms of his Fly Ball rates and pull rates the last couple of years in the minors, but he’s quickly found them again in Cincinnati. A bit of a head scratcher this trade, but given what we’re seeing across the system, it may be a reasonable assumption that Benson was just the odd man out in a 40 man crunch in the OF, and that the real target of the trade was Hajjar, not Boyd. But who knows.

What about our draft picks?

Our ‘22 and ‘23 first rounders are Chase DeLauter and Ralphy Velazquez. Both project as guys who can absolutely mash and have high raw power grades. Both came with question marks. For DeLauter it was injuries and the fact that he played at a mid-major school. For Velazquez it’s the fact that he’s a high schooler who appears to be severely limited defensively. Both question marks were enough to where these guys were available in the back half of the first round.

They acquired power while taking on risks that may have scared away other teams, the picks are gambles, but calculated ones.

Velazquez has also put up some incredible pull-side exit velocities at showcases and figures to have a pull-oriented approach despite not having any numbers to go off of yet.

DeLauter, on the other hand is interesting because while he has a high pull rate of 53.6% and an incredibly low oppo rate of only 14.3%, he has shown a very groundball oriented batted ball profile this year with rates above 50%. Because of his raw power and pull oriented approach I’m confident he’ll continue to get to his power in game and will learn to lift the ball more. Remember, he spent most of the offseason and a large chunk of this season recovering from surgery and has spent less time working with the minor league instructors as other players as a result. How those fly ball rates change over time (particularly the rest of this year) will certainly be something to watch for DeLauter.

Does this new philosophy mean that these are the only players the Guardians will ever acquire? No. It almost never works like that, but the guys that they acquire with high expectations attached to them all seem to fit this profile. It’s clear that the Guardians have found an approach that they like, but there’s a major question that still needs answered. We’ve seen that they can identify and acquire these guys, but can they develop them?

I have good reason to believe that they can

Player Development

There isn’t a take I’ve heard from Guardians fans more frequently than “we can’t develop hitting.” Personally I find that narrative to be overblown. Aside from the fact that in the run we made in the 2010’s Kipnis and Santana lived up to expectations while Brantley, Lindor, and Ramirez far exceeded them. I believe Chisenhall, had he been healthy, would’ve been another feather in the cap of Cleveland player development too.

But those days are long gone, we have a new hitting coach, and the only player left from those teams is Jose Ramirez. Our offense is terrible, so what reason is there to have hope for the Guardians ability to develop competent hitters?

For that I want you to turn your attention to a handful of players, 11 to be exact, 2 major leaguers and 9 prospects.

The Major leaguers in question are Andrés Giménez and Josh Naylor, both former top prospects acquired in trades from other organizations after they had already made their MLB debut. Both have developed exceptionally well. To be fair Giménez is having a down year and while I don’t think he’ll truly be the 140 OPS+ guy that we saw in 2022, I think he’s certainly better than the 94 OPS+ hitter we see this year. Naylor, on the other hand, has been arguably the best hitter in baseball not named Shohei Ohtani for the better part of 3 months. While the results haven’t come this year for Giménez quite like they have for Naylor, you can still see the influence Valaika and the new philosophy of hitting have had on both of their batted ball profiles.

The prospects we’ll be discussing are 9 players currently in the minors who have played a full season each of the last two years so that there’s enough data to see trends.

With this data we’ll be looking at two things.

What trends are we seeing?

What do these trends tell us about how the player is performing currently and what do they tell us about how they can be expected to perform in the future

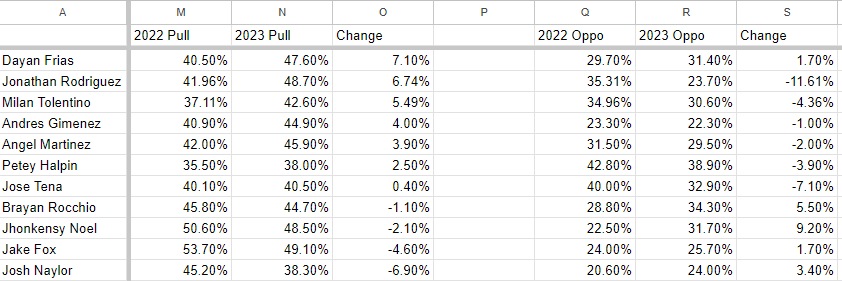

It’s spreadsheet time.

Again, a lot of numbers here, but they’re sorted in a way where a clear trend is visible. Of the 11 players being discussed, 8 of them have decreased their ground ball rate, and increased their fly ball rate. 6 players have decreased their opposite field rate, and 7 have increased their pull rate.

The first thing to note is that making adjustments as a hitter is difficult and things often get worse before they get better, this list reads like a list of people (except Rocchio) who got off to dreadful starts only to catch fire in the second half

Frias, Tolentino, Tena, Martinez, Fox, Halpin, Noel, and Rodriguez have all been on huge hot streaks in the second half. It’s reasonable to think that the first half struggles can be attributed to swing/approach changes having not “set in” yet and guys struggling at first to find ways to get comfortable with the changes. While it’d be unfair to say that these hot stretches represent the new normal for these guys, it’s reasonable to look at how well they’ve played and see the hard work paying off.

There are 4 individual cases I’d like to look at within this data.

Jhonkensy Noel is the only player on that list who has seen both his GB and oppo rates increase while his pull and FB rates decrease. This is definitely not what you’d hope to see out of Noel this year. The .7 GB/FB rate he put up in his breakout year in ‘21 certainly appears to be in line with what you’d hope for given what we know about expected stats and batted ball type, especially compared to the rate of 1.18 he’s produced this year. Fangraphs doesn’t allow for minor league splits on batted ball stats, but I’d be interested to see what his pull and FB rates have been since his hot streak started, my suspicion is that they’re improving.

Jonathan Rodriguez has been arguably the biggest breakout player in the system the last two years posting fantastic power numbers at high-A Lake County ‘22 and again at AA Akron this year, earning him a call up to AAA last week. While his ground ball to fly ball rate has gotten worse since last year, his infield fly ball rate has gone down by 6.5 percentage points (18.5% to 12%), so he’s hitting better fly balls despite hitting comparatively fewer of them. He has also dramatically decreased his oppo rate, dropping it by over 11!! percentage points. Its clear to see that he’s making improvements in line with what we’d expect if this truly is the new Guardians philosophy.

Josh Naylor is the first player in years to truly challenge Jose Ramirez for the title of best hitter on the team. Naylor put in a ton of work over the offseason and it has more than paid off. Nowhere is this work more evident than in his groundball rate which he has cut from 48.9% to 39.9%, that is a staggering improvement. Weirdly, he’s pulling the ball less than he ever has, however much of the work he did over the offseason was to address his most glaring weakness, his ability to hit left handed pitching. He’s talked at length about “keeping his front side from flying open” and “staying closed through the ball” it’s a safe assumption that the drop in pull rate has been a byproduct of that work to change his swing around to hit left handers more. It pretty clearly has paid off for him.

Andres Giménez has been somewhat of an enigma this year. After his breakout campaign last year he signed a massive extension to keep him here thru 2031, but since the beginning of this year his bat seems to have fallen off a cliff. He’s appeared to be close to breaking out for the better part of 3 months, but just hasn’t quite been able to put together any sort of extended hot stretch.

His fly ball rates have improved, but at the expense of his line drive rate, not his groundball rate. His pull rate has improved, but because he’s hitting fewer balls to centerfield, not fewer balls to the opposite field. He’s also chasing more, and making contact on pitches outside of the zone more frequently, inducing weak contact. Don’t get me started on the bunting.

In his breakout year in ‘22 he decreased his groundball rate by from 51.4% in ‘21 to 48.2% and his oppo rate from 28.3% to 21.8%. Giménez’ season has been a head scratcher to say the least. The career low exit velocity can easily be attributed to the increase in chase contact, and if there’s one encouraging thing, it’s that he is still showing an ability to get to his pull side power, having hit 10 home runs and a handful of doubles and fly ball outs that would have been home runs in a handful of parks. The player from last year is still in there, but right now he looks like a player that is overdoing it on the tinkering and hasn’t been comfortable in the box at any point. Time will tell if he gets back to the level of production Cleveland envisioned when they brought him in, but I’m cautiously optimistic that he’ll be able to.

The crazy thing about this profile is that the guy who fits it better than almost anyone is Jose Ramirez. They’re essentially trying to develop and replicate Jose’s profile across their system. Jose has made a career out of fly ball rates and pull rates that both exceed 50% allowing him to far exceed his raw power projections in game. It seems as though they’ve cracked the code on what has enabled Jose to be so successful and have found a way to teach players how to adopt that profile.

Conclusion

Look, nobody is saying this season has gone well, especially offensively. I wouldn’t blame you for being pessimistic about the future of this team, I honestly can’t remember a more frustrating season than this one. With that said, if you look past the surface, what you can see is an organizational shift in how we approach hitting as a whole. It seems the front office has a better grasp on what exactly leads to productive hitting, and has developed a plan to both acquire and develop the players to get the team where it needs to be to compete for a championship.

Are the Guardians going to come out next year and suddenly lead the league in home runs? Of course not, but would I expect us to be one of the worst power hitting teams in the league for the 3rd year in a row? Again, of course not. I haven’t seen nearly the level of production that I expected out of this team, however I now see the vision. This team is going all in on hitters who pull the ball and hit it in the air, and they’ve acquired more young players with high grades in raw power than in any recent stretch.

The team and the coaching staff keep insisting that the power is coming, that they’re not just preaching an approach of “just hit singles” to the guys. Honestly? I’m inclined to believe them, there’s tangible data showing that they’re acquiring hitters with a high likelihood of reaching their power potential, while working to maximize the power production of the guys already in the system.

Whether you attribute that to Valaika, Antonetti, the minor league staff, or any combination of the three, I feel confident saying that for the first time in what feels like forever, the Cleveland Guardians have a cohesive, competent approach to developing hitters that can lead to power production.

And I’m here for it.

MLB Pipeline is not necessarily known the most accurate source of scouting information available, however for the purposes of what we’re doing today, we just needed to operate in sort of a binary “has power” or “doesn’t have power” and being that it had the most easily accessible database of 20-80 grades dating back to 2012, it’s what we’re working with.

Technically speaking, 3 players didn’t have available grades on MLB pipeline, and I couldn’t find 20-80 grades for them anywhere else. However for all three, Martinez, Freeman, Arenado, all of their written scouting reports say they have at least “above average to good power” so we can safely assume at least a 55 grade.

Because stats for batted balls mean that every PA ended in a ball put in play (notably, no walks) OBP can be lower than batting average because sac bunts, sacrifice flies, etc. count as plate appearances, but not at bats.

https://theathletic.com/4579492/2023/06/04/guardians-hitting-coach-chris-valaika-offensive-struggles/

Just an outstanding post. Tons of data and detail and super well written. Particularly interested in the thoughts on the Jones and Benson trade, both of which were odd to me. Not a twitter/X person, so looking forward to more!.

Matt, we have spent every spring in AZ since 2015. We go watch almost daily as we have to drive by the facility to go almost anywhere. Anyhow, only 1 year did I ever witness this at the Indians. It was E’s first year there, he was taking swings with a screen positioned so close to his body that it forced him to bring the bat down to clear the screen & it resulted in greater lift. If he wud swing more level it wud hit the screen and stop him. After that, I looked for that at other facilities we visit. I did see it at Mariners, Texas and once at White Sox. I assumed he was working on fly balls at the time. I have never seen it again at the Guardians facility, but then they have not opened it up since Covid. All the others facilities are full6 open and this spring, I saw Reds minor leaguers doing the same thing